Human vision is based on movement. The human eye is always moving, even when it is seemingly still. It undergoes ocular microtremors, a constant vibration not detectable without special equipment. As vision is based on movement, this sensory information is reliant on differentiation from a static background. Without this differentiation, the result would be blindness. Human hearing also works on this principle of differentiation. Notice that when you move from a noisy party to a quiet hallway, many sounds that were previously lost in the background become detectable. In fact, all five senses work on this principle.

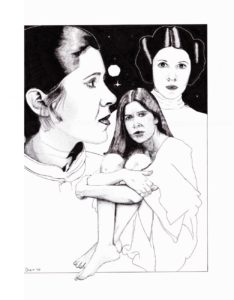

So does human emotion. The healthy mind moves fluidly through a plethora of feelings on any given day. From happiness to anger to sadness, ad infinitum, we feel that which we feel in relation to other feelings. Now imagine if all that rich emotive experience were to cease. The result would be emotional blindness.

In other words, the result is depression.

***

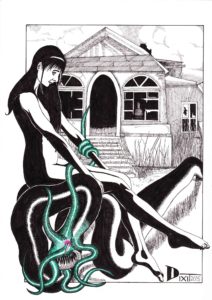

I can usually feel a depressive phase approaching like a locomotive. I am caught helpless on the tracks as the world loses all of its shiny allure. I lie down and feel the loss of feeling, itself. Some might argue that a lack of emotions should convey some advantage. It does not. I feel a gray nothingness. The world seems leeched of color. Food tastes like ashes; music becomes a cacophonous jumble of unrelated sounds; attempts at sexual arousal end in disappointment. Any attempt to find pleasure ends in failure.

When I’m in the grip of deep depression, I endlessly recall all of the things I have done wrong, and foresee all of the things I will do wrong. Sometimes there are tears, but they fail to bring relief. This is Milton’s Paradise Lost. I have tumbled into depression and “long is the way and hard, that out of the Darkness leads up to the light.”

Typically, while I am depressed, hours of sleep accrue with interest. After twelve to fifteen hours of constant slumber, I find myself slept out. Thereafter, I sit in my reading chair with my forehead cupped in my hand, trying to think myself into a better place. I have tried for thirty years to use positive thoughts to lift me up. I’ve also tried deep breathing, meditation, and good old-fashioned hard work, all to no avail. Clinical depression is melancholy boredom magnified 100 times. It consumes 40,000 lives each year.

***

I’ve been told that “it’s all in your head,” “snap out of it,” and by one well-meaning friend that I am “really talented. Shake off the shadows.” These comments ignore the biological basis of my depression.

As I’ve grown older, the lows have gotten lower. Medication provides some relief, but often, psychiatric medications stop working after a while. Each year that I age, I take another turn around the downward spiral of longer and more intense major depressive episodes.

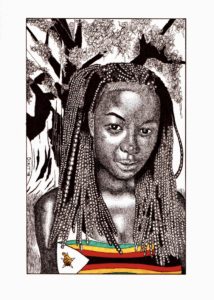

If there is one simple antidote that occasionally works, it is affection. Especially verbal affection from someone who understands. That, at least, relieves the isolation.